Discover how to read a Chilean wine label with this easy guide. Understand regions, grape varieties, and pick your perfect bottle with confidence!

So, you’re ready to delve into Chilean wines. Great! I’m sure it’s because you’ve been reading some of my previous articles, right? But you’re looking at the selection in your wine shop or supermarket and it’s… it’s quite a lot, isn’t it? You’ll find weird names like Colchagua and Limarí, words like Reserva or Costa. And what even is a Carménère?

Take a deep breath and relax. I’m here to help you understand how to read a Chilean wine label with ease.

The good news is that you probably won’t go wrong with whatever you end up selecting. Chile makes a lot of delicious and easy to drink wines, but are their labels easy to read as well? Spoiler: they are, but they give you a lot of information. Let’s talk about it!

Many things can be in a Chilean wine label, but there are a few things that have to be there. It’s the law. This essential knowledge will help you learn how to read a Chilean wine label

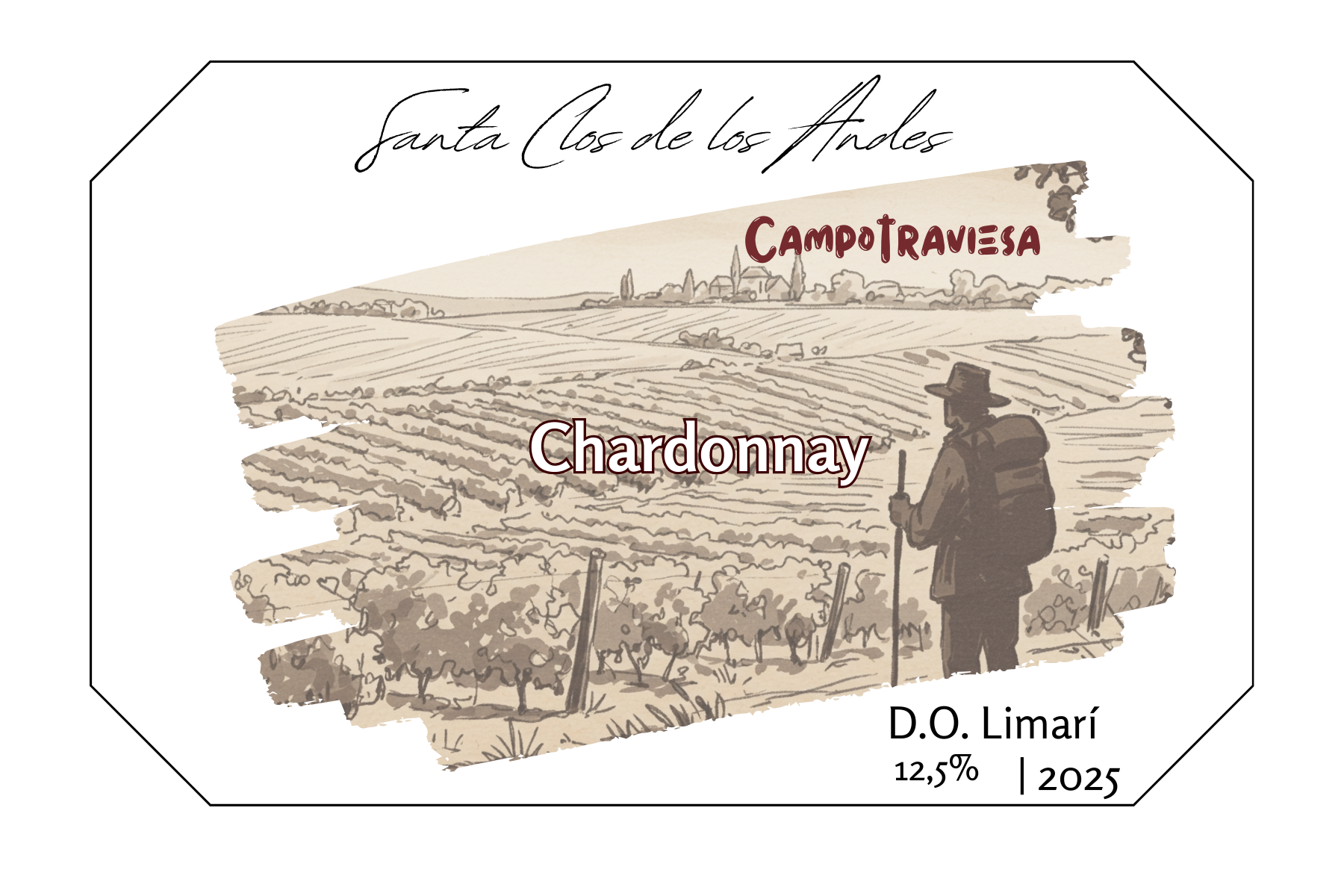

Above: fictitious label for a Limarí Chardonnay. Below: How to read a Chilean Wine Label

Alcohol Content

You’re probably surprised to find this one first, before region or grape variety. See, Chilean law is particular about the subject. To call your fermented grape juice “wine”, it must have a minimum 11.5% ABV[i]. Surprisingly high, right? It’s different, of course, for imported wines. Some winemakers in Chile are lobbying to lower that value. Climate change has pushed them to explore suitable regions further south[ii], but the colder temperatures prevent fruit from developing enough sugars for fermentation.

The 75% Rule

A Chilean wine label can only list a grape variety, region, or vintage if at least 75% of the wine comes from that source. Many wineries exceed this requirement, using 85% or more to meet stricter European Union standards. While vintage is a big deal in some Old-World regions, Chileans emphasize it less. Instead, focus on how old the wine is when choosing your bottle. Remember most wine in Chile is meant to be drank young.

Like other New World wines, in Chile, grape variety is more prominent than specific regions, but I think it’s worth it to talk a little bit about them.

How to Read a Chilean Wine Labels by Understanding Regions

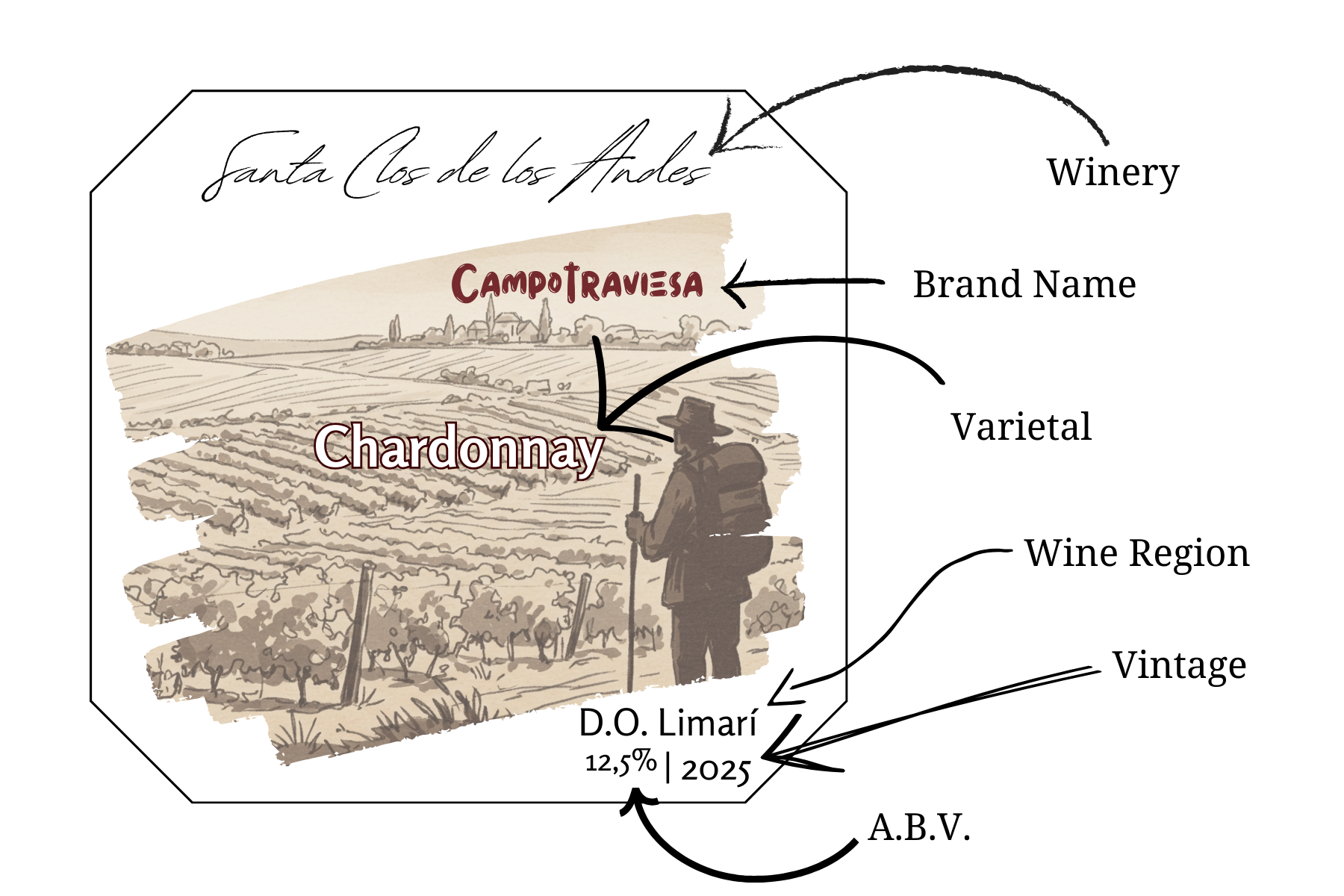

Front label of a Chilean Carménère from Cachapoal

This topic is extensive enough and merits its own article. Here I will give you the skinny. Generally speaking, wine regions to the north are warmer and drier, whereas southern regions are colder and more humid. Look for Syrah from northern regions, like Limarí and Aconcagua. The Central Valley is where Chile gets its reputation. For reds, Colchagua and Maipo are the valleys for Carménère and Cabernet Sauvignon, and Casablanca is where you will find your Sauvignon Blanc or Chardonnay.

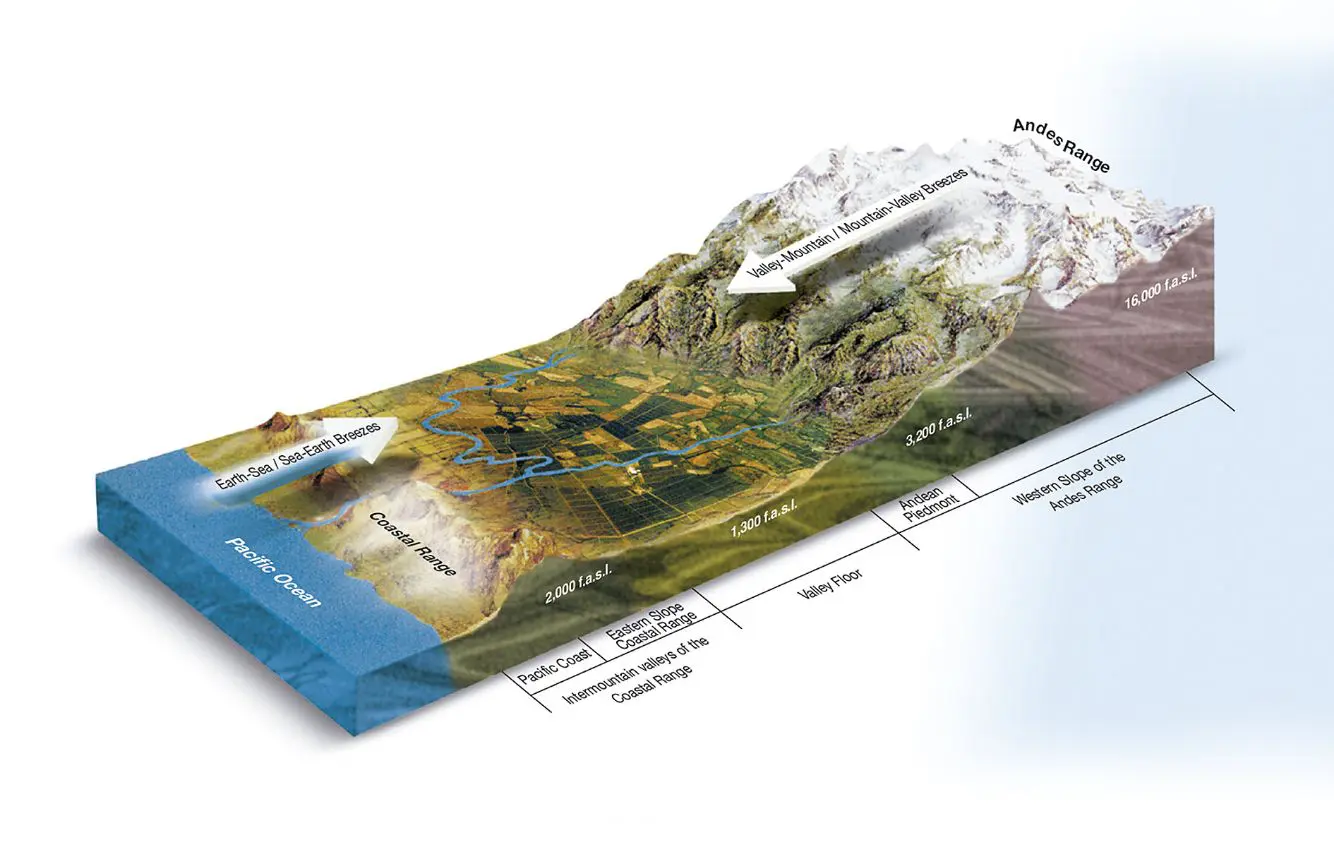

Altitude in the east—the Andes Mountains—and the Pacific Ocean to the west clearly define these valleys. The higher the altitude, or the closer to the sea, the colder the region. Keep that in mind if you’re looking for more elegant wines. Finally, to the south you find more independent winemakers and grapes that you might have not heard about, like Carignan, País, or Cinsault.

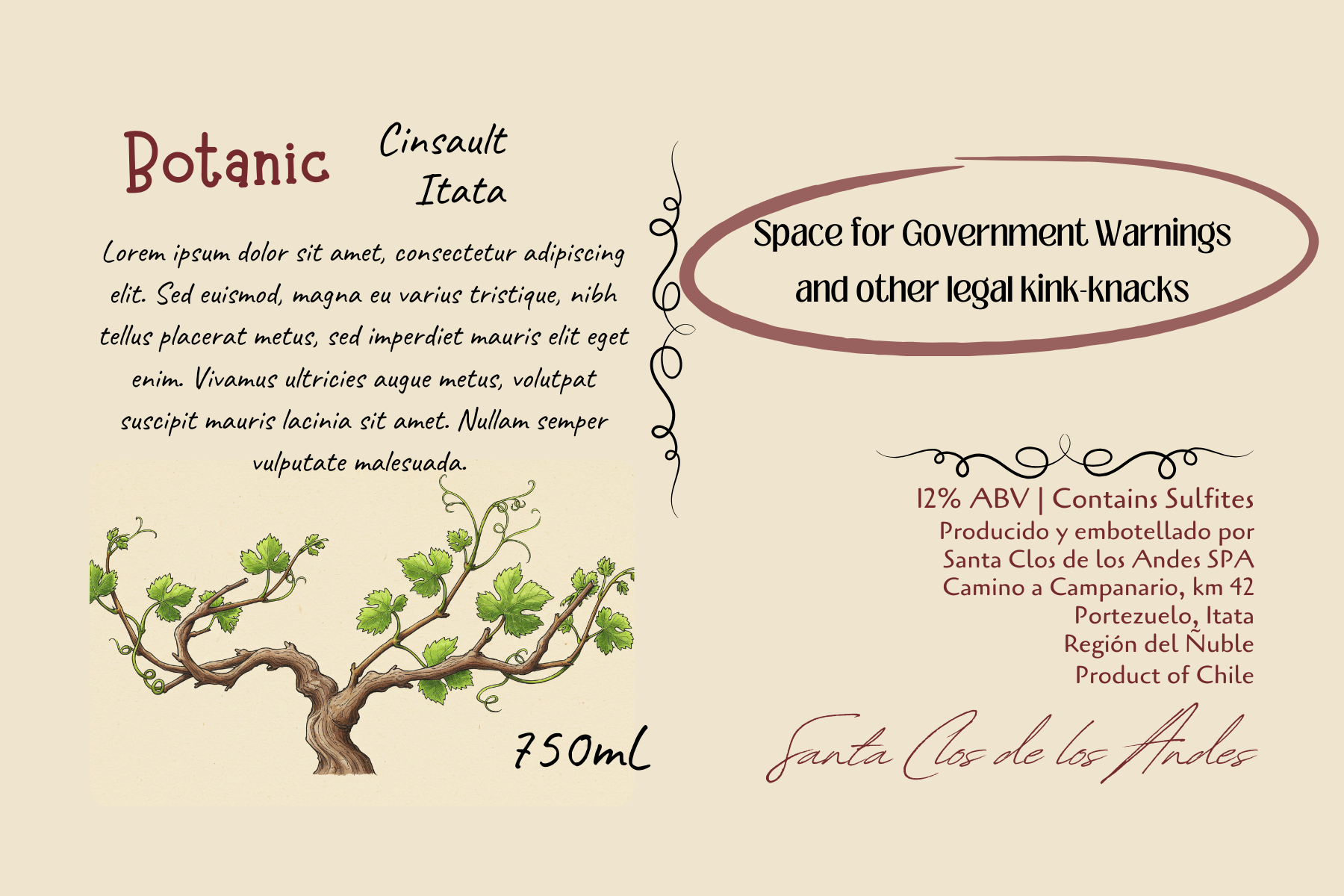

The back label of a Chilean Cinsault from Itata

A Few Other Things to Help You Read a Chilean Wine Label

By law, the amount of wine in your bottle, in milliliters, must be written down in the label, even if it’s obvious by its shape and size. Labels also need to add the producer’s name and address, as well as the brand name, where applicable.

There’s some additional things that wineries can choose to add to their bottles. Some of them are helpful, while some are… well… marketing.

There’s this unofficial geographical segmentation of regions from east to west, but wineries largely ignore it. It’s, however, super helpful, and I wish they would use it more:

Andes

Chile’s eastern border in the majestic Andes Mountain range. Winemakers plant vines in its slopes. Here you’ll find high altitude wines, with some vineyards at 2,500 meters above sea level. These vines receive more sunlight during the day, but nights up in the mountains are colder. Grapes develop thicker skins, interesting complexity and pleasant acidity. Some of the country’s premium wines blend Cabernet Sauvignon grown in the slopes of the Andes.

Entre Cordilleras

“Between Mountain Ranges” is the translation, and that’s literally what it is. These vines grow in the valleys between the Andes and the coastal mountain range. This is the widest wine area, and varies in climate significantly from north to south, but it’s—by and large—warmer and you can expect fruitier wines. If you’ve had a juicy Carménère before, it was probably from this area.

Costa

Past the coastal ranges you find these valleys. They cool down with sea breezes and are influenced by the ocean. You can find crisp wines with a hint of salinity. This is also the name you’re more likely to find in labels—more than Andes and Entre Cordilleras—, especially in whites like Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc. But you shouldn’t overlook Pinot Noir grown in these valleys.

Reserva and Gran Reserva

Often you will find the word “Reserva” in your wine’s label, surely that means it’s undergone some aging in wood, right? And there’s also “Gran Reserva”, which sounds grander, and therefore longer aging? Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Neither aging nor wood are mentioned in the regulations when dealing with Reserva and Gran Reserva. If you’re trying to figure out how to read a Chilean wine label, be aware that ‘Reserva’ doesn’t necessarily mean oak aging. See, you can forego the whole process altogether, as long as your wine is more alcoholic. That’s right! Wine with 0.5% more alcohol than the minimum required can be called Reserva. And if it has an additional 0.5%, then it can be a Gran Reserva[iii].

Am I saying that these terms are meaningless in Chile? Mostly, yes. However, within the same brand, they mean that the winery thinks the Reserva is of higher quality than the varietal. Strange, right? What do you think of this law?

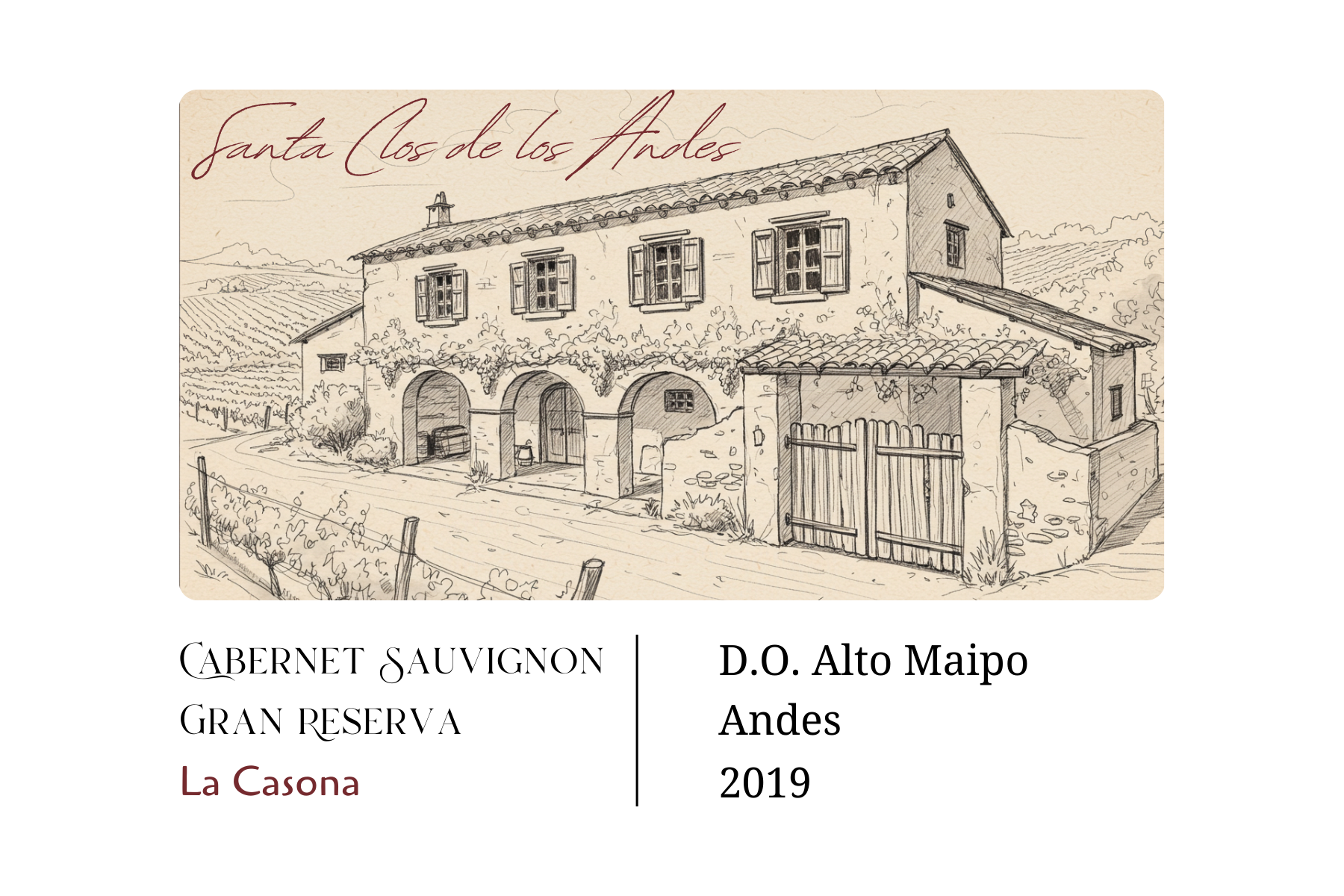

Label for a Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon from Alto Maipo. Alto—”high”—refers to altitude.

Final Few Knick-Knacks in How to Read a Chilean Wine Label

Somewhere in the front—or back—label you will find the name and address of the winery. And I mean the legal name, not the fantasy one. In newer wines, if purchased in Chile, you will also find a warning about the dangers of alcohol consumption. Labels must also state on the label if the wine contains sulfites.

Labels might also feature some art, whether simple a drawing of the estate or a painted masterpiece by a local artist. A well-chosen piece of art will cater to the target market. It’s the same with the fantasy name of the wine, if it even has one. Lastly, you might find some verbal flourish about the aromas and quality of the wine. Sometimes it will tell a nice story, and it can guide you with the wine’s bouquet, but as a rule, feel free to ignore it.

The Last Drop

Were you familiar with Chilean wine-labeling laws? What do you think about them? There’s a lot there to unpack there, I know, but I wanted to be thorough. Chilean wine is fun and easy to drink, so don’t be intimidated by its label; the important stuff is straightforward. Now you know how to read a Chilean wine label, go ahead and try a new wine! If you already know how to read a Californian—or pretty much any New World—wine label, you’ll feel at home with Chilean wines. The obstacle is getting to know the wine regions and some uncommon[iv] grape varieties.

Still, I encourage you to take the plunge and get yourself a bottle of Chilean wine. Chances are you won’t regret it. What was the last Chilean wine you drank? Let me know in the comments! Mine was a Sauvignon Blanc from Casablanca. I had it just a few hours ago, with lunch. It’s summer here, when I’m writing these lines, and it’s Saturday.

Photo by Eduardo Gabriel Padilha

Footnotes

[i] Alcohol By Volume

[ii] Not sure if this needs clarifying, but “south” means heading to colder weather.

[iii] Remember, the minimum required by law for wine to be wine in Chile is 11.5% alcohol. Therefore “Reserva” wines must be at least 12% ABV, and “Gran Reserva” ones at least 12.5%.

[iv] Your mileage might vary, of course. What’s uncommon to some is someone else’s bread and butter.

Cover Image: Reading Chilean wine labels. Photo by Toàn Van

Leave a Reply