From tough soils to water deprivation, winemakers intentionally want stressed vines to produce higher quality and tastier wines.

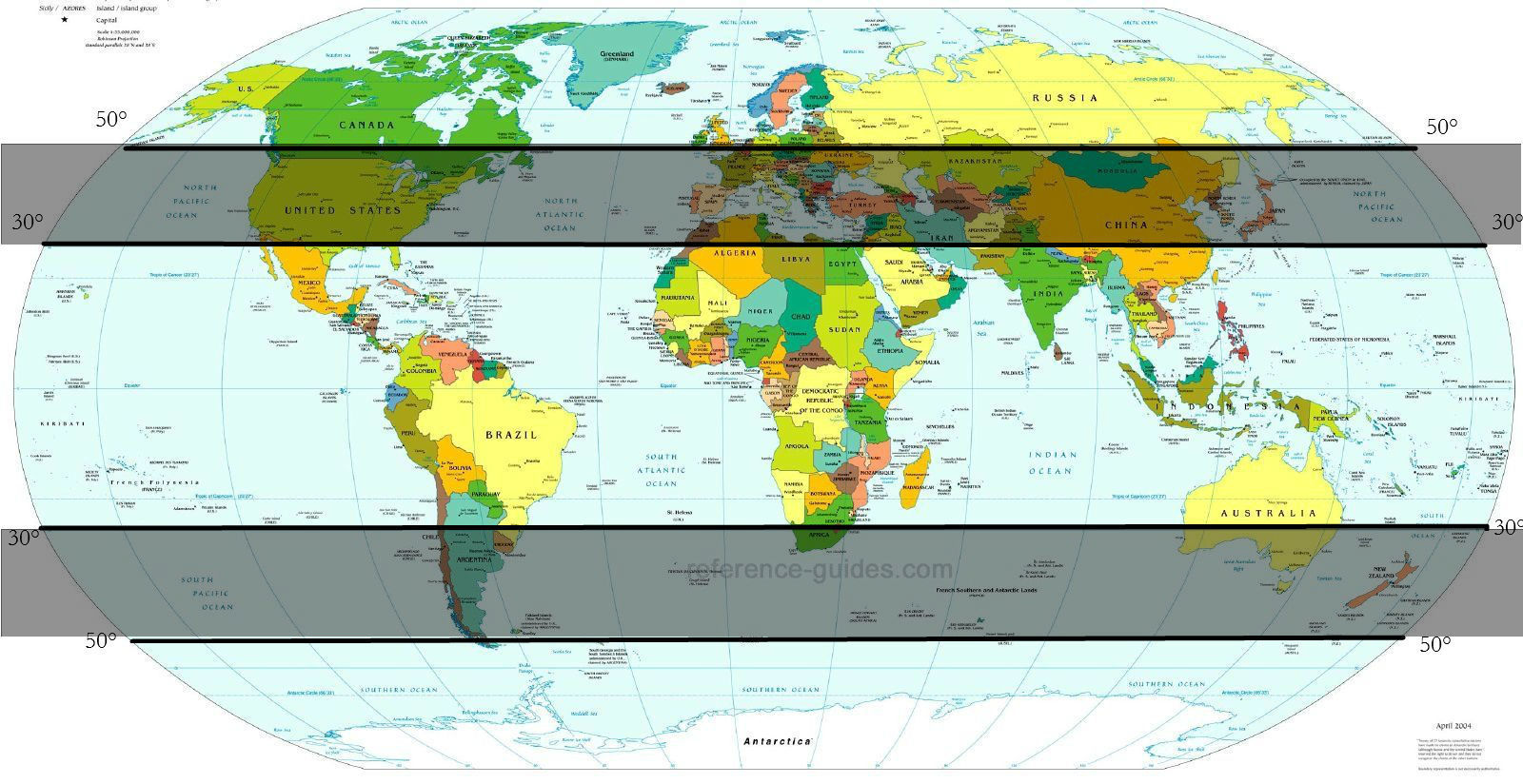

I have an interesting one for you today, so buckle up! Grapes enjoy moderate temperatures. Plenty of sun during the day and cooler—but not freezing—nights. Enough water to grab mineral from the fertile soils to feed on and grow to live healthy and happy lives. They flourish between certain latitudes north and south of the equator[i], looking for areas that are not too tropical, not too arid, and not too close to the poles. Grapes, in short, like a relaxed temperate life. You’d think, then, that winemakers give those comfortable conditions to grapevines, right?

Wrong.

Stressed Vines are Better for Making Wines

See, winemakers actually want grapevines to suffer so they, the plants, concentrate their energy on the berries. When vines are comfy, they distribute energy evenly. They don’t need their fruit attracting birds because the plant found a good place to grow and thrive. On the other hand, they want to make grapes sweet and flavorful when they feel the survival of their offspring depends on birds taking their seeds to better soils[ii].

Naturally, those are the grapes preferred by vintners to make their wines, so they purposely stress the vines by planting them in difficult soils, starving them (thirsting, really) by denying them water and pruning the plants. Let’s unpack further each of these techniques to understand how a particular stress affects the vines.

Pruning Plants? How Does It Affect Grapevine Stress?

Yeah, let’s start here. In winegrowing, pruning means selectively cutting-off old canes[iii] from last season’s growth, leaving fewer buds to produce fruit for the next harvest. Pruning takes place in the winter, because that’s when the vine is dormant.

To better understand how this stresses vines, let’s imagine an unpruned one. More canes mean more leaves and more buds. Leaves, of course, photosynthesize[iv] the sun’s energy. So, when there are fewer of them, the plant needs to find other sources of nutrients to fully ripen the grapes. In other words, it’s easier for the vine when there are more leaves. Furthermore, the plant will distribute its energy—read sugar—evenly amongst all fruit. More fruit means there might not be enough energy for them to fully ripen. With less berries, conversely, energy distribution is not as diluted, resulting in more flavorful grapes.

Depriving Vines of Water Has Some Benefits

I was in Tuscany during the particularly hot and dry summer of 2022, and I remember some vintners wondering if the authorities would let them water their fields[v]. See, Chianti Classico regulations forbid irrigation. All the vine’s water must come from rainfall and whatever the roots can find underground.

This is typical in many wine regions. Winemakers want the vines to work extra hard finding water, because that will result in smaller but more flavorful grapes. Same as we talked about above, the stressed vine concentrates its energy to make berries sweeter. Remember the birds! If there’s too much water in the soil, whether due to irrigation or excessive rainfall, the typical result will be larger and watery grapes lacking in flavor and sweetness. You will notice most winegrowing regions are on the dry side[vi].

Photo by Congerdesign

How Different Soils Make Stressed Vines

Grapevines are often planted in soils that are not particularly fertile. If they have easy access to water and nutrients, they get lazy. That’s the theme for today’s article. Winemakers don’t want their vines’ roots to stay shallow, because then they will concentrate on growing leaves instead of developing flavorful grapes. Furthermore, they want to challenge the roots’ ability to find available water. That’s how soil types come into play.

Talking about soils in winemaking can get complicated and geeky, and I’m not an expert on the area, so I will keep this as simple as possible. I will divide soils into three broad categories, but please keep in mind that in vineyards, you won’t find one of them, but typically a combination of two or all three of them. In fact, this is desirable because different soils contain different nutrients. Since roots are struggling to find them nearby, they must go hunting for them. Varied nutrients equal more complexity in the flavors of the wine.

So, for the purpose of this article only, let’s break down the three categories:

Water-Retentive Soils

Soils like clay or silt hold water tightly. Think of it like a sponge, water is available, but not easily free-flowing. Vine stress comes because roots have to work harder to get to it. Not like squeezing that sponge. No, that would be too simple. An accurate way to think about it would be that the roots are trying to pull small magnets (electrically charged water) from a much larger magnet (the soil). You can find examples of clay soils in Bordeaux’s right bank, as well as the Rutherford sub-region in Napa, famous for the Cabernet Sauvignon they produce there. In Chile, we have the Colchagua valley, where you’ll find great Carménères.

Soils With Good Drainage

Here we’re talking about limestone, gravel, or volcanic soils. Water from rainfall or irrigation is available for the vines, but it it doesn’t stick around for long. Roots have to work hard to rapidly grab whatever water they can before it drains away. Imagine you’re drinking a milkshake with a straw, but the glass has holes in them. If you don’t work fast, you will not get enough of that tasty strawberry goodness! You can find well-draining soils in Champagne and Chablis, as well as some areas in Tuscany. In California, winemakers typically Grenache from Paso Robles in this category of soil. As for Chile, it would be Casablanca, where winemakers produce world-class Sauvignon Blancs.

Rocky Soils: The Wild Card of Vine Stress

Some rocky soils drain water well, but they still deserve a special paragraph because drainage only presents extra stress for the vine. The real challenge here is that water can be free flowing and available for the plant but roots still have to navigate around stones to reach it. Furthermore, there’s physical rocks where you would normally find soil, so there’s less of it available for the vine!

Who would think to even plant in that, right? Well, the best Old World examples are Châteauneuf-du-Pape and the Douro valley in Portugal. You will also find that some of the best Pinot Noirs from the Willamette valley in Oregon grow in this soil. Closer to home—my home—you’ll find it higher up in Maipo valley. Also, high altitude wineries in Mendoza use this soil for their excellent Malbec wines!

The above paragraphs show the tip of the iceberg. Let me know if you’d be interested in a deeper dive where we can really geek out about wine soils and other terroir subtleties!

Cool! So, stressed vines make better wines. Got it! But there are risks, and it’s best not to overdo it.

Dangers of Overly Stressed Vines

Winemakers gotta be smart about how much stress to put on their vines. Too much of it can end up damaging the plant. Stressed vines struggle to find nutrients, but that can make them more susceptible to disease[vii]. When not enough water is available, stunned growth can be expected, and with it, reduced yield.

Moreover, if vines are pruned excessively, grapes risk getting exposed to too much sun, and sunburn can cause imbalanced flavors. And that’s the key. Winemakers look for balance in everything they do, including vine stress.

The Last Drop

From soil selection[viii] to when and how much to prune and whether to water the plants or not, winemakers have tough decisions to make every year. Funny to think that the goal of those decisions is to make life harder for vines. Of course, vintners must control stress carefully to avoid going overboard and damaging the fruit. The real goal, then, is to make flavorful wine.

Did you know about the hardships suffered by vines in vineyards around the globe? I think it’s interesting how much the fruit benefits from controlled stress. Within reason, vine stress truly is great for wine! Are you a geek like me and find all that soil stuff interesting? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Photo by Markus Winkler

Footnotes

[i] It’s often understood that wine grapes grow best between 30° and 50° latitude on both sides of the equator. Climate change is challenging this convention, however, and wine regions are gradually moving further north in the northern hemisphere and south in the southern one.

[ii] A watered-down grape is less attractive to the birds. Vines will happily allow fruit to fall to the ground and grow right there. Remember, in this example, the soil is fertile.

[iii] In vines, a cane is a branch.

[iv] If you remember from science class, photosynthesis is a process in which the plant’s leaves absorb sunlight and use it to convert water and carbon dioxide into food.

[v] It ended up raining late that summer, so no irrigation was needed, which in turn produced better wine! Stressed vines was a constant, though

[vi] There’s some exceptions, of course. Notably, Rias Baixas in northern Spain has a lot of rainfall, but they still produce banging Albariños. In Chile, the Osorno region, one of the southernmost areas in the country, is also rainy, and they also make great wines.

[vii] Less nutrients can weaken the plant. Like you and me, a weak inmune system makes us more vulnerable to bacteria.

[viii] This only applies when planting new vines, of course.

Cover image: Red wine glass in a vineyard. Photo by Grape Things.

Leave a Reply