Read about the resurrection of Carménère: believed to be lost in the 19th century, it found a new home in Chile, and helped shape its wine story.

“There is more history than geography in a bottle of wine.”

– Jean Kressman

Are you familiar with Carménère? Have you seen this grape variety while shopping for your next red wine? Maybe you’ve even tried it already! Are you familiar with its fascinating history, though? Below I will go into it, or at least into the resurrection of Carménère in Chile. But first, if you’re new to this grape, let me give you the CliffsNotes.

Carménère is one of a handful of Bordeaux grapes approved to be used in their reputed blends. The varietal shines when skilled winemakers can decipher the appropriate harvest time. When done right, you can expect:

- A smooth red wine of medium body and nice acidity.

- Wonderful fruit aromas ranging from raspberry to plum.

- An herbaceous undertone is frequent. A hint of green bell pepper and even jalapeño.

- Refined tannins.

- From the oak you should expect some smokiness, leather scents, and sometimes a little cocoa.

I will go into more detail elsewhere. For now sit around the fire and listen to the tale of the resurrection of Carménère.

Photo by TomBen

A Grape Once Lost, and Then Found

Not to get too deep in the history of Chilean wine right here, but after Chile gained its independence from Spain, and because it had already a somewhat robust wine industry, it turned to France for grapes and know-how. In the mid 1800s, several Bordeaux grapes arrived and were planted in Chile, Carménère being one of them. Now, it might’ve been a case of miss-labeling, communication error, or just plain negligence, but the Carménère grapes got planted next to—and mistaken for—Merlot.

French grapes thrived in the Chilean weather, and that was a good thing, because after a devastating plague attacked and decimated vines in Europe, and the industry only survived by bringing back plants from the Americas!

So, ok, I might’ve gone too fast there. Let’s back up a little and slow down.

The blight I’m talking about is phylloxera[i], likely native to tropical climates in Central or South America. Phylloxera resistant American vines carried the small insect with them when shipped to Europe during the second half of the 19th century. Unfortunately, European vines were not immune, so phylloxera spread rapidly in France and the rest of Europe.

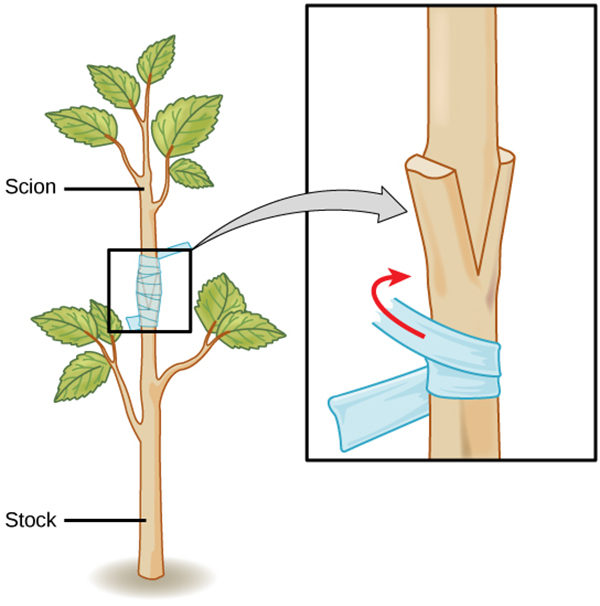

It eventually got back to the New World and started to affect vineyards here, attacking the very same non-resistant French vines brought over just a few decades before! The bug ruined entire crops, and it took several decades for an effective plan to be implemented. Turns out, the solution was to graft[ii] European scions into American rootstocks. European varietals, vulnerable to phylloxera, would grow normally from the scion, but the bug would not affect the roots of the American vines.

Bah Gawd That’s Chile’s Music!

This is the part of the story where Chile gets the hot tag for the save. Since a lot of the Bordeaux plants had been destroyed by the insect, Chile sent vines to France to be grafted into waiting American rootstocks. You see, Chile was spared from phylloxera because it is a very isolated country, with the Pacific Ocean to the west, the Andes to the east, and the Atacama Desert to the north. Pristine vines from Chile (and other places in the New World) were sent to France to restore the vineyards affected by the blight.

The Resurrection of Carménère (Pretty Much) Only Happened in Chile

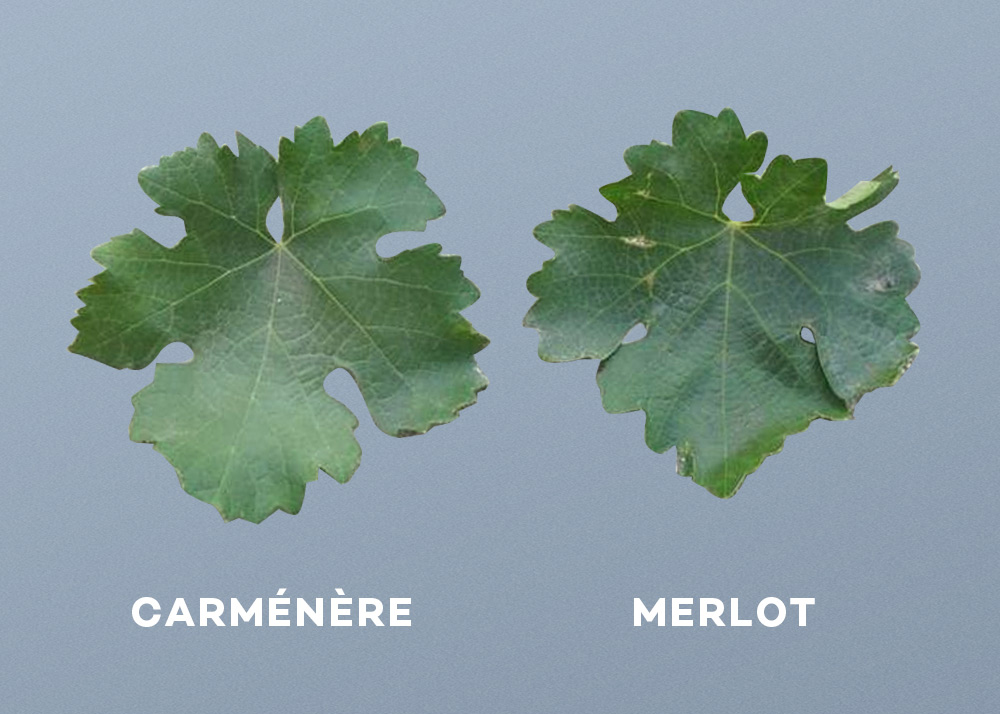

So, does this mean that Carménère was brought back to France from Chile at the end of the 19th century and things went back to normal? Well, not quite. Bordeaux went back to producing their excellent blends without it. And Chile kept growing its wine industry bottling Merlot and what they thought was Merlot. All of that lasted until 1994, when French ampelographer[iii] Jean-Michel Boursiquot visited Chile. He was invited for a congress, which included visits to several wineries. They were walking through some fields when he noticed that the planted vines there had leaves and flowers inconsistent with Merlot[iv].

I must pause here to give credit to Chile. Some of the growers were already aware that their vines were probably not Merlot. Also, they quickly accepted their slipup and moved to have the new grape registered in the corresponding institutions and started bottling them with the right label. More so, Chile used the resurrection of Carménère as a beautiful story to boost the varietal’s appeal and has done a terrific job in marketing it.

Today, Chile is known in the wine world for bringing a grape varietal back from the death. More hectares of Carménère are planted in Chile than anywhere else in the world. Furthermore, the wine is still gaining strength worldwide, quickly becoming the signature wine of Chile.

Or, at least, that’s the story being told to market Carménère wine around the globe.

“Never Let the Truth Get in the Way of a Good Story” – Mark Twain[v]

As it happens, Carménère wasn’t as extinct as the story says[vi]. Some (not many, but some) vines survived the phylloxera plague in Bordeaux and other places in France. Not only that, but they could also be found in other parts of the world. There are reports of the grape planted in both Australia and the state of Washington before 1994. Also, Carménère has a similar story in Italy, where it was confused with Cabernet Franc.

Ok, so the Carménère grape was not technically extinct. Fine. But surely those other places only plant a small amount of it, right? Yes. Chile is the country where more hectares of Carménère are planted. Unless you count China. Yes, China. The reality is that China likely has more of the varietal planted than Chile[vii]. They use a different name for it, and some of it might not actually be Carménère, but evidence suggests that they do plant more of it.

Wait, is The Resurrection of Carménère a Hoax?

What are we saying, then? Should Chile recant the story of Carménère? I say absolutely not. For one, it makes a lovely story, and even though it’s not strictly the truth, it’s also not very far from it. No, the varietal was not completely wiped out, but it was in Chile that it found its best expression, and there’s enough of it planted in the country to make it internationally available to the rest of the world.

In a way, they did revive the varietal, didn’t they?

As for China having more Carménère planted than Chile, that will only be a problem if and when they figure out a way to break into the international markets. I’ve been hearing about China becoming the next big thing in wine for the better part of the last decade[viii], but it still hasn’t happened. For now, I think it’s fair to say that Chile has made better use of their Carméneere in the world’s markets than China. So no, no apology needed. Chile should still be allowed to tell their story for marketing purposes. Of course, like with any other story, it should be taken with a grain of salt.

Photo by SplitShire

How Come France Don’t Want Me, Man?

One last thing about the resurrection of Carménère that’s worth talking about. If it was not wiped out in France, and they had to import it back after it was “re-discovered” in Chile in 1994, how come so little of it is planted in Bordeaux? Is it still used in blending?

The second answer is easy. Yes, Carménère is still used in small amounts and not by every winery. Less than 1% of planted grapes in Bordeaux today are Carménère, but that might change in the future, if the popularity of the varietal continues to gain renown.

The first question is a little more complicated, and there are likely many factors to explain why it has fallen out of favor in France. Let’s begin with some facts about the plant itself. It’s finnicky. It ripens late, it likes plenty of sun and dry weather. It is, in other words, better suited for conditions in Chile than in Bordeaux.

Also, it took around a century for Carménère to be correctly identified in Chile. In those years, Bordeaux wine had already rebuilt its wine industry without this varietal, and their award-winning blends didn’t include it. Grafting might also have been an issue. Unlike Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot, the plant did not respond well to grafting, as it started producing erratic yields. It was probably not worth the risk to bring back the plants to France from Chile.

Lastly, what if modern winemakers tasted Carménère and said “yeah, no, I’ll pass”. And hold on, before you start typing that hateful comment. I’m not saying Carménère is a bad wine. It’s just difficult to get it right. If picked too early, wine made with it will have strong bell pepper aromas, and if picked too late it will be too fruit forward and alcoholic. For the amount that was historically used in their blends, Bordeaux oenologists might have said it was not worth clearing a field here and there to plant it back. Their palates got used to their wine without Carménère, and I think that´s an unlikely but fair assessment.

The Last Drop

When I first moved to Chile and got interested in wine in the early 2000s, Carménère was not too popular. It was just another red wine varietal with a French name difficult to pronounce and even harder to spell. The first few ones I tasted were, in all honesty, disappointing.

They had not yet found a balance between the green bell pepper aromas you get when the fruit is picked too early, and the overwhelming fruit you get when harvested late. Those wines also suffered from too much time in the barrel, making them too woody and tannic. I was fortunate to see the growth of the vintners and how they transformed the grape into a smooth well-balanced wine.

There is no doubt that this grape, though it may have roots in Bordeaux, found its true home in the central valleys of Chile. Did you know about Carménère’s journey from near extinction to becoming a symbol of Chile’s wine industry? I think it’s such a cool story of rediscovery, adaptation, and foresight. This resurrection of Carménère makes a trully inspiring story. Today, that history continues to shape Chilean wine culture. Whether you’re a wine connoisseur or just curious, there’s no denying the unique place Carménère holds in the world of wine. Have you tried this revived grape? Share your thoughts below!

Photo by Marcelo Leal

[i] I try to keep things informal in the main text, but if you are interested, you can learn more about this devastating insect by reading what the Wine & Spirit Education Trust wrote about it.

[ii] Grafting is basically joining the tissues of two plants to make them grow as one. The upper part is the scion, and it maintains the desirable characteristics from that plant, whereas the lower part is the stock, which in this case is the phylloxera resistant part. I was looking for a good illustration to show you what grafting is, but could not find It with wine, so I leave you this one which I’ve borrowed from Morning Chores:

[iii] Ampe-what? Ampelography is concerned with the identification of grapevines. It does so through a thorough study of the plant: leaf, flower, berry, etc. In modern times, of course, it is helped by DNA testing. Wein Plus has a great description of this field of science, and you’re welcome to read it here.

[iv] Merlot and Carménère’s grapes look somewhat similar, I guess. They are also both medium body wines of similar color, kind of. Both varietals share some flavors and aromas. People just thought Carménère was a very different clone (though in those times they would’ve likely not call it that) of Merlot. Check this photo of both leaves side by side, from the phenomenal folks at Wine Folly.

[v] He might have not said that. I’ve not been able to find a convincing origin of the phrase. But it doesn’t matter. Sounds cool. Use it!

[vi] Alvaro Tello did the research and published it in the excellent Chilean online wine news magazine WIP. You can find the whole article here. It’s in Spanish, but it’s not too difficult to translate articles online, and this one is worth the read, if you’re into well researched information.

[vii] Even in 2024, at the time of me writing this article, it’s hard to find exact information about how much of what is planted in China. But even in 2014, Patrick Schmitt wrote for The Drinks Buisness about the subject. It includes the thoughts of a familiar name: ampelographer Jean-Michel Boursiquot.

[viii] I’m not sure when you will read this, but I’m writing the article in 2024, and publishing it in early 2005. By the time you get to it, I might look like a fool and China is already an important player in the wine world. Time will tell. Still, I don’t think this will change the narrative about the resurrection of Carménère.

Cover Image: A path through Carménère vines in Colchagua. Photo by me.

Leave a Reply